Finding the right words

Enhancing your discussions with patients

Tweaking sentences or adding short statements to your explanations can present information in a way that is most helpful for patients.

For example, specifically telling a patient the usual duration of cough (21 days) can be especially helpful in addressing patient expectations of when they will likely feel better. This is more convincing for patients than saying symptoms will get better in "a few days".

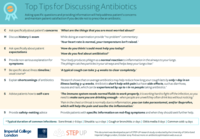

The CHESTSSS acronym below was developed and tested in a randomised-controlled trial [1] which resulted in improved antibiotic prescribing and patient satisfaction when used by experienced GPs in the UK.

CHESTSSS presents specific communication techniques. These techniques have been developed based on patient expectations and needs specific to antibitoic discussions so can be more useful and effective than general approaches (e.g., 'ICE' or 'Calgary-Cambridge' models).

CHESTSSS can help you to remember specific phrases which:

- reassure patients

- increase patient understanding and satisfaction with a prescribing decision

- avoid re-consultations

- may be particularly helpful for patients who are expecting antibiotics.

Read examples of phrases to say in your consultations below and/or click to download a brief summary of this information:

What some prescribers might say/do:

You may feel that a good history is enough to find out what the patient’s concerns are. But research looking at audio-recorded consultations has found that the identification of the patient’s main concerns was often omitted [1]. In addition, patients often complain that their main concern has not been addressed.

Consider:

Asking the patient specifically about their concerns. This can be difficult as, if not careful, one can sound patronising or give the impression that you have not been listening. However, if concerns are not specifically asked about, the patient will sometimes not share their main worries for fear of being seen as ‘overly-anxious’.

Example phrases you can use:

‘There are probably a number of things that are worrying you about this illness, but what would you say are the things that you are most worried about?’

‘You’ve mentioned the high temperature; is that the thing that is causing you most worry at the moment, or is it something else?’

‘When you feel like this it can be pretty worrying, and I just want to make sure that I have a clear understanding of what you are most worried about at the moment. Is it the cough that is worrying you most? Or perhaps there is something else worrying you?'

What some prescribers might say/do:

A good history and examination, conducted prior to providing the patient with advice and/or reassurance, is an essential component of reassuring patients that their illness is being taken seriously.

Without a thorough examination patients may think that you have missed a serious illness and may feel "fobbed off", especially when being told: "it's just a virus" [6].

Consider:

Providing a "running commentary", especially a "no problem commentary" [7,8], to the patient while doing an examination, for example:

'Your heart rate is normal', 'Your temperature isn't raised', 'Your lungs sound good."

What some prescribers might say/do:

Research has shown that there is often a mismatch between what GPs think patients are expecting and what they actually want [9,10].

The only way of actually knowing what patients want or expect is to ask them. A patient that appears ‘demanding’ may actually just want reassurance that the infection has not ‘gone down to the chest’, rather than antibiotics.

Consider:

Asking the patient specifically about their expectations, for example:

'How do you think I could most help you today?'

'Some people have a clear idea about what they are expecting when they come to see me. Is there something that you were hoping for or expecting that we haven't talked about yet?'

'It's helpful if I know your thoughts, and I was just wondering what you think about antibiotics?'

What some prescribers might say/do:

Telling patients that you can find no sign of serious illness when they are worried about symptoms, might not be enough to make them feel reassured – they just think you have failed to detect how serious their illness is!

Consider:

Finding out what symptoms the patient is concerned about and then providing convincing non-serious explanations for these symptoms [7,8]. For example:

‘Your body produces phlegm as a normal reaction to inflammation in the airways to your lungs. The phlegm catches particles in your airways and helps keep your lungs clear.’

It can be helpful to acknowledge that these non-serious symptoms can still be very disruptive for patients so showing empathy that they are feeling very unwell is important.

What some prescribers might say/do:

Prescribers might not always set realistic expectations and sometimes suggest that patients will get better ‘in a few days’, when we now know that it often takes much longer than this to recover.

In addition, patients often have unrealistic expectations about how quickly they will recover, and these can lead to unnecessary anxiety and re-consultation.

Consider:

Research [11-14] has provided us with valuable information on expected duration of common infections. It is useful to tell these durations to patients to reassure them that their symptoms are not unusual.

For example: 'A typical cough can take 3-4 weeks to clear completely.’

| Infection | Average duration of illness |

|---|---|

| Middle ear infection | 8 days |

| Sore throat | 7-8 days |

| Sinusitis | 14-21 days |

| Common cold | 14 days |

| Cough or bronchitis | 21 days |

The 'Treating your infections - RTI' leaflet provides these durations so you can use it when discussing it with your patients.

What some prescribers might say/do:

Prescribers don't always discuss pros and cons of antibiotics with patients, and patients often are not aware that antibiotics have no or very limited benefit for several common infections.

Consider:

Several trials have shown no or limited benefit of antibiotics for several types of common infections. Antibiotics are not usually indicated in sore throat, sinusitis, acute otitis media and acute cough where pneumonia is not suspected.

- Antibiotics make little difference to illness duration:

Patients are very surprised to learn how minimal the average effect is. Antibiotics may shorten the duration of cough by one day in an illness lasting up to 3 weeks [15].

- Receiving more antibiotics (longer durations and multiple courses) can increase levels of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, an effect which may persist for up to a year [3-5]:

This is something that patients do not realise, and provides patients with a much stronger motive for avoiding antibiotics than just telling patients that unnecessary prescribing affects antibiotic resistance in general.

- Antibiotics have side effects:

Common side effects of antibiotics can include diarrhoea, nausea and skin rash. These can be experienced by up to 1 in 10 people who take antibiotics [16].

- Antibiotics do not help pain:

Sometimes patients think that antibiotics will help with pain. You can advise patients to take full courses of paracetamol/ibuprofen (see the self-care advice below).

Example phrases you can use:

‘Research shows that on average antibiotics may help reduce how long your cough lasts by only 1 day in an illness lasting 3–4 weeks. Antibiotics don’t help with pain but have side effects, such as diarrhoea, nausea and rash, which can be experienced by up to 1 in 10 people taking antibiotics.’

Most patients are looking for something positive that they can do to feel better more quickly.

Consider:

Asking patients what they have done already to manage their symptoms and reassure them that what they are doing will help. Giving reassurance and advice on other things they can do can go a long way to make patients feel more in control and comfortable.

Reinforcing the fact that the patient’s own immune system is their best source of defence, and advise on what they can do themselves to help their body fight the infection. Patient leaflets can support how you discuss self-care advice.

Example phrases you can use:

'Drink enough fluids. The immune system needs normal fluids to work properly. The immune system is working hard to fight off the infection, so you need to make sure you are drinking enough – when people are unwell they often eat and drink less without noticing.'

‘Pain in the chest or throat is normally due to inflammation, so you can take paracetamol, and/or ibuprofen, which will help the pain and soothe the inflammation.’

Lastly it is important that patients understand what they should be looking out for, and when they should re-consult.

Consider:

Providing patients with specific information on 'red-flag symptoms' and advising them on what to do if symptoms get worse.

Supporting the safety-netting advice by discussing a patient leaflet.

Finally, it can be useful for you to summarise key messages - the natural history, reassurance that nothing serious is going on (assuming you have found no indication for antibiotics) and to check that the patient understands and is happy with the management plan.

Fitting antibiotic discussions into your consultations

It can be helpful to see how other prescribers fit discussing antibiotics into their consultations. Click on the videos below to see a GP (Dr Nick Francis) discussing and using this approach. These videos are from a free online course "TARGET Antibiotics - Prescribing in Primary Care" which you can sign up to here.